Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Friday, November 18, 2011

Conspiracy Theory as a Setting: Initial Thoughts

This post may be a bit more rambling than usual. I think I tried to put too much in it, so sorry for the length.

I have been always fond of alternative histories. Given the number of novels, books, films and series trying to depict how the world could look like if some things went differently, I am not the only one. From the sci-fi series like Sliders, through Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, to academic books based on complex simulation models, many of us seem to take comfort in this act of exerting control over history, which at the same time has this nice, sensationalist tang.

From the perspective of a “non-believer”, conspiracy theories are exactly such a thing; to most o us, they are fiction and we read them as fiction. Some of them, especially those created in the last couple of centuries, are complex enough to create such alternate realities. However, instead of being different due to some important event going another way, they are so because of the existence of a secretive conspiracy guiding world events.

Here lies the crux of the matter – conspiracy theories can very easily become world-building texts. When watch movies or read books by Alex Jones, Peter Joseph or David Icke we invariably hear that what we see and hear on a daily basis is a lie – the true reality, history, even spirituality, is hidden from us, replaced by a lie used to keep us in check. Moreover, the apocalyptic nature of conspiracy theories allows their author’s to create future scenarios – Alex Jones would herald the decimation of humanity, while David Icke a new step in spiritual evolution. For clarity I will refer to them as “Deny Everything” and “The Truth is Out There” strategies.

|

| Dark City (1997) |

The “Deny Everything” approach supposes that the conspiracy is pivotal to the setting and that the PC know that the everyday life is just a facade. Both the Matrix and Dark City did that, even though none of these movies scream to you “conspiracy theory”. Incidentally, the movie Conspiracy Theory is also an example of this, with the protagonist's tormentors being just a rouge unit of a cancelled government program. The notion here is to go head on and make every conspiracy theory or urban legend true, like The X-Files and the upcoming MMO Secret World did.

What I find most interesting though are not the themes, but what people do with the worlds created by conspiracy theorists. “The Truth is Out There” (TTiOT) strategy relies on those effectively ready-made setting. TTiOT is a strategy of trying to show what would happen if the conspiracy won or progressed their plans. In popular culture, examples could include the first Deus Ex game, with its imagery of a world ravaged by both terrorism and a new plague. We, as the protagonist, soon learn that all of this is a part of a plan to bind all of humanity under one monolithic organization, with references to FEMA easily implying the contemporary conspiracy theories. A foreshadowing of this can be found in the recently released Deus Ex: Human Revolution.

Both the Deus Ex franchise and Eclipse Phase is an ideal example of the clever use of a particular plan becoming reality. Within the latter's setting humanity was essentially decimated during a war with rouge Artificial Intelligences. When I first read it, it just screamed “New World Order” at me. The basic premise is similar as in Deus Ex, but here the contemporary is less pronounced.

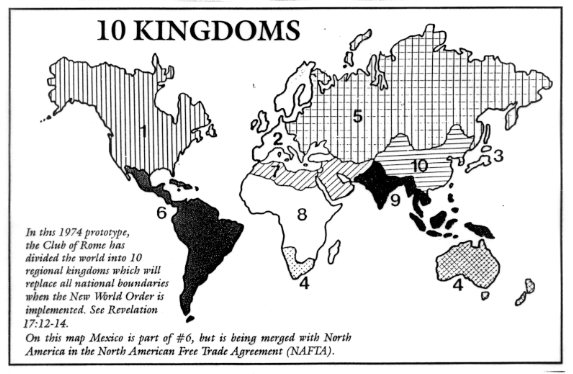

So what is the vision of the NWO here? Essentially the one I came across in a number of texts can be summed up thus: The NWO is a globalist conspiracy that plans to control the world through corporations and extranational institutions, downgrading the importance of nation states. They control the development of technology, plan to decimate humanity or make it docile through pharmaceuticals. Environmentalism is also on their agenda, as they want the planet clean, but only for themselves. The end goal of the NWO is to install the selected few as rulers of the Earth, virtually immortal through technological apotheosis.

The ideas in Deus Ex seem to be directly inspired, but some echoes can be found in EP as well, giving rise to interesting (though a bit non-canon) speculation. Was the rise of the T.I.T.A.N.s a fluked attempt of NWO seizing power? Did it succeed, rendered transhumanity divided and helpless with the techno-elite waiting to deal a final blow (the number 95 per cent appears both in EP and in conspiracy documentaries)? Is the Fall really a sham, with large territories of Earth quite intact, though obscured and defended by killsats?

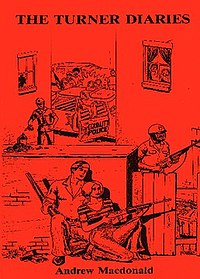

Curiously enough, conspiracy theorists do that as well. One notorious example are the Turner Diaries, a book published in 1978 by William Luther Pierce under the pen-name of Andrew MacDonald. Full of overtly racist content, the text describes a world in which the white race had most of its civil rights taken by an Afro-American and Jewish ruling class. Those rulers inflict all sorts of injustices on the whites, which leads the protagonist to become a suicidal terrorist fighting for white supremacy. Sounds like racist science-fiction until you realize that the book is effectively a propaganda tool showing what would supposedly happen if the liberal mindset was left unchecked by “heroic” neo-Nazi and post-KKK activists.

Curiously enough, conspiracy theorists do that as well. One notorious example are the Turner Diaries, a book published in 1978 by William Luther Pierce under the pen-name of Andrew MacDonald. Full of overtly racist content, the text describes a world in which the white race had most of its civil rights taken by an Afro-American and Jewish ruling class. Those rulers inflict all sorts of injustices on the whites, which leads the protagonist to become a suicidal terrorist fighting for white supremacy. Sounds like racist science-fiction until you realize that the book is effectively a propaganda tool showing what would supposedly happen if the liberal mindset was left unchecked by “heroic” neo-Nazi and post-KKK activists. Another interesting theme is turning fiction into reality. I was quite surprised when one of the conspiracy documentaries claimed that Aldous Huxley's Brave New World is not a dystopian vision, but an account of what will happen to humanity if the conspiracy, of which Huxley was a rebel member, would not be stopped. In a fascinating reversal, these are claims that the conspiracy theory inspired the fiction that, in truth, inspired the conspiracy in the first place.

And this brings us to a topic I wanted to explore for a long time, namely the dynamic of a conspiracy theory, utopia and dystopia. This one will be more academic and theoretical, but hopefully interesting. After that I hopefully will give you a working example of a campaign based on the principles above.

Sunday, November 6, 2011

Conspiracies in Popular Culture: Eclipse Phase RPG

A word of warning – this entry will be the first in a series about the role of conspiracy motifs in role-playing games, pen-and-paper ones to be exact (RPG). If you do not know what they are you are missing a lot, and you may find these posts a bit confusing. For this, I apologize.

Now, the topic of how to use conspiracies and, more importantly, conspiracy theories, in RPGs has been on my mind for quite some time. Admittedly, there are a multitude of games that deal with this motif, either as an element of the setting, or as the axis around which the game revolves. Of the RPGs I know, the former could be the World of Darkness series released by White Wolf or FFG’s Dark Heresy and Black Crusade, as well as Warhammer Fantasy Role Playing. It can easily be found in any corporate setting, from Cyberpunk to Shadowrun. Examples of the former would be Paranoia, Conspiracy X and, to some degree, Eclipse Phase (EP), to which I will return in a moment.

Now, the topic of how to use conspiracies and, more importantly, conspiracy theories, in RPGs has been on my mind for quite some time. Admittedly, there are a multitude of games that deal with this motif, either as an element of the setting, or as the axis around which the game revolves. Of the RPGs I know, the former could be the World of Darkness series released by White Wolf or FFG’s Dark Heresy and Black Crusade, as well as Warhammer Fantasy Role Playing. It can easily be found in any corporate setting, from Cyberpunk to Shadowrun. Examples of the former would be Paranoia, Conspiracy X and, to some degree, Eclipse Phase (EP), to which I will return in a moment.

Truth be told, most RPG allow the usage of conspiracy theories and conspiracies, with some it will fit better, with others less. And here really lies the crux of the matter – how do I, as a GM, employ the conspiracy (theory) to benefit the plot and make it more fun. A number of approaches can be taken:

1. The conspiracy theory is just a background, which may incite a feeling of paranoia among the PCs, but nothing more. The problem here is that unless the game is of the second type, this “flavour” will soon be lost due to more down-to-earth concerns, or be simply a quirk of some PC.

1. The conspiracy theory is just a background, which may incite a feeling of paranoia among the PCs, but nothing more. The problem here is that unless the game is of the second type, this “flavour” will soon be lost due to more down-to-earth concerns, or be simply a quirk of some PC.

2. The conspiracy is the antagonist – a shadowy group that the PCs strive to defeat and destroy. This would be the most standard application, different from any other RPG antagonist because of an air of secrecy.

3. A mixture of both, which would follow the pattern of spy movies or series like The X-files. Here the players would fight a conspiracy, only to find that these are only patsies of some greater power, which becomes the new antagonist. I tried to write such campaigns a number of times, but ended up dropping the motif. On the one hand, they can easily turn into a repetitive “monster of the week” sort of thing,

These would be the most obvious ones, but there is one more option:

4. The players are the conspiracy (theory). Believe it or not, at some points most of the campaigns will result in such a scenario. Don’t believe me? Let’s see... The PC will plot and conspire against the NPC, forming a tightly knit cabal intent on gaining more power and influence. Does sound familiar, right? What makes it even funnier, is that some RPGs, Eclipse Phase amongst them, encourage a similar style of play.

Point four, after some deliberating made me think of Richard Hofstadter again. In “The Paranoid Style...” essay he mentions one thing I failed to address in the previous posts. Namely, he notices that the conspiracy theorists (the enemies of the conspiracy) often form groups extremely similar to those they claim fight. Examples are numerous – Adam Weishaupt modelled the structure of the Bavarian Illuminati (the historical ones) on that of the Society of Jesus, while the members of the far-right John Birch Society formed “cells” just like the supposed Cold War Communist infiltrators. The reason, as other scholars suggested is that the theorists, deep in their hearts, want to emulate the conspiracy they are fighting against, to feel as all-powerful and in control as their enemies.

And then in struck me: It is not the Game Master who should look how to use conspiratorial motifs, but the players. For the GM they are a problematic motif, for the PCs they are tons of fun.

And then in struck me: It is not the Game Master who should look how to use conspiratorial motifs, but the players. For the GM they are a problematic motif, for the PCs they are tons of fun.

Eclipse Phase, to my mind, is the perfect demonstration of how all the motifs describe above converge. Granted, I currently GM one campaign focused more on gatecrashing (exploration of other planets through stargate-like artefacts) than conspiracy, but with a setting like that conspiracy is almost a must. The tagline of the game is, after all, “roleplaying game of post-apocalyptic transhuman conspiracy and horror”. The introductory chapter of the book defines all of these themes, including what a conspiracy theory is:

‘To conspire means “to join in a secret agreement to do an unlawful or wrongful act or to use such means to accomplish a lawful end.” As such, a conspiracy theory attributes the ultimate cause of an event or a chain of events (whether political, societal or historical) to a secret group of individuals with immense power (political clout, wealth, and so on) who hide their activities from public view while manipulating events to achieve their goals, regardless of consequences. Many conspiracy theories contend that a host of the greatest events of history were initiated and ultimately controlled by such secret organizations. Of equal importance is the silent struggle between clandestine groups, waging a secret war behind the scenes to determine who influences the future.’

I love this definition. Of all that I have seen (non-academic ones at least), this is the best so far. What is great is that it immediately, though discretely, defines what is important for the game. Notice the last sentence; it is not something you would find in your typical anthology on conspiracy theories. We, as potential players and GMs learn what will be the focus of a conspiracy-heavy Eclipse Phase campaign – a “secret war behind the scenes”. This war, as the setting's most recent sourcebook Panopticon demonstrates, is not a lost cause, for transhumanity has even more means to detect groups trying to remain hidden than we have today.

But, just for the sake of it, let’s go through the points above in relation to EP:

Point one is easy enough. The book itself tells us that “the Fall left behind a persistent legacy of fear. This has faded over the past decade, but a great many humans still unconsciously expect the other shoe to drop and the TITANs to return at any moment”. So, the PCs can explore, smuggle, or play a political game, but the fear will be there, in the background, vocalised by some of the more paranoid NPC. It will, however, have little to with the plot itself.

Point two can be used in a number of different ways. For a game that focuses so much on conspiracy, there are few “obvious” conspiratorial antagonists (in the sense of the Illuminati or the New World Order of our real world). The choices are, however, many. From the defined potential baddies of the Hypercorps and Project Ozma, through the followers of the TITANs, to the mysterious Prometheans. The problem here is that most of them would work in a rather similar manner; a better use would come through...

Point two can be used in a number of different ways. For a game that focuses so much on conspiracy, there are few “obvious” conspiratorial antagonists (in the sense of the Illuminati or the New World Order of our real world). The choices are, however, many. From the defined potential baddies of the Hypercorps and Project Ozma, through the followers of the TITANs, to the mysterious Prometheans. The problem here is that most of them would work in a rather similar manner; a better use would come through...

... point three, with the Hypercorps controlled by TITAN loyalists, who in turn are infiltrated by agents of the Prometheans, whose shadowy masters so far remain hidden. This is potentially the most fun version, with the PCs not really fighting the conspiracies, but rather trying to find out whether they pose a threat to transhumanity. This is, after all, the PC’s job in the generic EP campaign.

This brings us to point four, which seems the generic setting of the game. A typical EP group will be members of “Firewall”, a secretive organization that identifies and eliminates what they believe are threats to transhumanity. This part really blew my mind – these guys are exactly like the counter-conspiracies described by Hofstadter. They have a very rigid structure, opaque even to its own members. Field operatives, called “sentinels” are “soldiers of Firewall, the reserve troops called to instant active status whenever danger is perceived”. Just like the minutemen, or Communist agents, they live normal lives until they are told to go on a mission. Their “handlers” are called “proxies”, people who run the organization full time and have different roles, though no centralized leadership. Firewall can be quite nasty in their decisions, sacrificing human life if they feel the cause is just. They are different from their enemies only because they claim they’re “doing the right thing”.

There you have it, ladies and gentlemen. In Eclipse Phase, you are a member of a conspiracy waging a secret war against other conspiracies, with the continuous, paranoid feel that the more crazy conspiracy theories may turn out to be true, and all s*** will break loose.

The game is really fun and well researched, which many of my co-players confirmed. From my perspective, it is one of the best uses of the conspiracy theory motif in a work of popular culture. It avoids the fetishization of the term, escapes the worn-out cliches, and tries to answer the question how would conspiracy theory making and conspiracies work both in-world and for the players rolling the dice. By looking at this one slice of the setting, we can tell a lot about its culture, and it can give us lots of fun.

The game is really fun and well researched, which many of my co-players confirmed. From my perspective, it is one of the best uses of the conspiracy theory motif in a work of popular culture. It avoids the fetishization of the term, escapes the worn-out cliches, and tries to answer the question how would conspiracy theory making and conspiracies work both in-world and for the players rolling the dice. By looking at this one slice of the setting, we can tell a lot about its culture, and it can give us lots of fun.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)