Having read the title, some of you will have no idea what I am talking about, while the rest might have the wrong idea. An explanation is forthcoming, though some additional reading might be required to get what I am trying to say here. Also, minor spoilers ahead.

First, the Horus Heresy is a series of sci-fi novels set in the world of the war-game Warhammer 40.000, a setting created by Games Workshop and its publishing house, Black Library. The Heresy, set in the setting’s past, is essentially a galactic rebellion led by Horus, a genetically engineered superhuman, against his maker and father, as seemingly immortal being known only as the Emperor. The Emperor first unified Earth and promptly began to re-conquer its colonies across the Galaxy, ushering an age of science and reason. The Heresy, hoverer, effectively buries any hope humanity could have of becoming a prosperous, pan-galactic empire, and instead plunges it into the thrall of a totalitarian theocracy, technological obscurantism, and millennia of perpetual war. It is chockfull of epic betrayals, momentous battles, father issues, and subtle allusions to contemporary history.

What I would like to talk about today is one of such allusions, which are actually a large part of Games Workshop’s milieu. So I am not arguing that the company and its writers are in fact agents of the Illuminati who, through hidden symbols, subliminal conditioning and programming, and other such devices further the goals of the conspiracy. That’s a job for Madonna or Alex Jones (who claimed in one movie that “Brave New World’s” author was in fact a whistleblower who depicted the final plan of the globalist conspiracy). Rather, I would like to demonstrate how conspiratorial/historical elements were quite artfully used in one of the Horus Heresy novels.

“Horus Rising” by Dan Abnett, one of the most acclaimed BL writers, was the first book of the series. I won’t go deep into the plot, suffice it to say that the protagonist, Captain Garviel Loken, a leader of a military unit – a company, which is part of Horus’ Legion, the Luna Wolves, learns that a shadow society exists within the Legion itself: the Lodge.

At this point, many readers would connect “lodge” with “Masonic”, and they would be right. Abnett’s reworking is what most would find familiar. The Lodges, supposedly present in some other Legions, are a place and society where everyone is equal, regardless of rank, and where members can talk freely about matters of import. It is not religious in any sense, though shrouded in secrecy. Furthermore, Loken’s dislike of such societies mirrors those voiced in anti-Masonic literature since the 18th century; historical Masonic lodges were supposed to have their own laws, were a root of favouritism, and a place to plot and conspire.

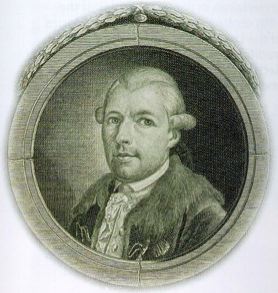

|

| Adam Weishaupt |

|

| "John Robinson" by Henry Raeburn (1798) |

As mentioned, Games Workshop loves to put tongue-in-cheek references to our times in their books and games. They range from suggestive names, through characters modelled on historical figures, to plots of entire Warhammer books being a reworking of classic fiction. What I loved about the Horus Heresy Masons/Illuminati motif was that the authors at the same time made it quite subtle, but at the same time, once you “get” the motif, the analogy is striking and this realization actually helps to understand the plot and its context better. It is the perfect example of a conspiratorial motif nicely embedded into a work of fiction.

P.S. It should be noted that Adam Weishaupt, the historical creator of the Bavarian Illuminati, indeed “infiltrated” Masonic Lodges, but only to attract members to his secret society. While today it would probably be considered guerrilla marketing and bad taste, it had nothing to do with world domination.