|

| Taken from xkcd.com |

To say that the terrorist attacks on September 11th, 2001, remain a thorny subject would be an understatement. Same goes for most American conspiracy theories as viewed by Americans. While I've limited experience, most of my conversations on this topic with people living in the U.S. fall into two categories: some are quite enthusiastic and share their own thoughts, while others are very tight-lipped, with the second group visibly bigger when I try to raise the more recent events, like 9/11.

I particularly recall one conversation in which my interlocutor suddenly snapped something about the „crazy bastards” of the 9/11 Truth Movement (9/11TM). Granted, it is hard to be an „inside job” believer after November 2001, when President George W. Bush effectively called the propagators of 9/11 conspiracy theories culprits of the terrorists, and in front of the UN Assembly no less. It may seem obvious that such people wanted respect for their tragically deceased countrymen, one that cannot be denied. There are, however, factors other than recentness that make the 9/11 conspiracy theories and their reception unique.

The problem with interpretations of 9/11 is that it can become quite easy to believe the conspiracy „theory” version, while the official one, even though branded as „truth”, can be much harder to stomach. The confusion is heightened when we realize that the two versions have much structurally in common. This is the claim made by Peter Knight, a University of Manchester scholar, who compared the 9/11 Commission report to the supposed “ravings” of conspiracy “nuts”. As it turned out, the vision of highly competent terrorists, who outwitted the CIA, FBI and many other governmental acronyms fits the definition as much as the “inside job” theories do. But that could be a topic for another post.

So, to the point. To accept the official version one has to accept that the U.S. can be a world superpower at one time, but totally helpless when it comes to national security on the other. The first part is easy enough; actually, it may have accounted for why so many Americans stood behind G. W. Bush during the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, as well as initially accept the Patriot Act. The reason, as Elizabeth Anker argues in her yet unpublished book, seems quite simple – the society needed someone strong to identify with and able to combat the new threat. You can stock up with guns as much as you want, but you cannot fight a terrorist with them, while he can strike at you from the mountains of Afghanistan. It is the second part that brings problems – how could such a mighty state be so helpless? The official narratives, the 9/11 Commission report most notably, favored the “failure of imagination” line, stating that no part of the Federal government or the armed forces should take the blame, for an idea of ramming a skyscraper with a jet plane was inconceivable.

So, to the point. To accept the official version one has to accept that the U.S. can be a world superpower at one time, but totally helpless when it comes to national security on the other. The first part is easy enough; actually, it may have accounted for why so many Americans stood behind G. W. Bush during the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, as well as initially accept the Patriot Act. The reason, as Elizabeth Anker argues in her yet unpublished book, seems quite simple – the society needed someone strong to identify with and able to combat the new threat. You can stock up with guns as much as you want, but you cannot fight a terrorist with them, while he can strike at you from the mountains of Afghanistan. It is the second part that brings problems – how could such a mighty state be so helpless? The official narratives, the 9/11 Commission report most notably, favored the “failure of imagination” line, stating that no part of the Federal government or the armed forces should take the blame, for an idea of ramming a skyscraper with a jet plane was inconceivable.

Now, if you believe that the American government was in some was directly responsible for the attacks, either by allowing them to happen or doing the deed themselves, the situation is fully reversed. Since the “bad guy” is the government, one does not need to fear the terrorist. This, I believe, could be read between the lines of the comments regarding Osama bin Laden’s death, especially those claiming he was never really killed. While I’ve not encountered any that stated it outright, the veracity of this event is irrelevant – for the “conspiracy theorist” bin Laden was just some invented patsy, that may have been long dead before the 9/11 attacks (a claim that appears in one of the versions of “Loose Change”). Now, since I do not believe in the terrorist threat, the argument goes, I do not need any protection from some organization, I can deal with the “real” culprit on my own terms and turf with my guns, the voting ballot, and the Constitution, the true laws of the land passed to me by the Founding Fathers.

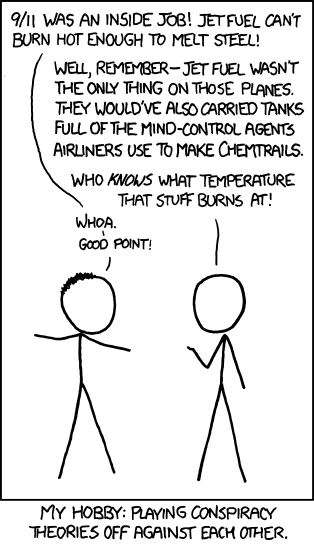

This process, while not true in every 9/11TM, demonstrates how conspiracy theories give acceptable answers. They may not be the truth – in fact many of those reading them will not treat them as gospel. Rather, for a slight moment of guilty pleasure, they will feel the world is not the random, excessively complex machine the postmodern age made it to be. For it is important to remember that no black-and-white distinctions exist when conspiracy theories are concerned. Most of their audience will be people, whom the theories will amuse, provoke to think on the topic, or simply evoke laughter. Few, in fact, would be committed to join a rally or a “truth movement”; most seek comfort. And to end on that note, here is one of my favorite quotes from any academic paper on conspiracy theories, one written two years prior to 9/11:

[Those who believe in conspiracy theories] are some of the last believers in an ordered universe. By supposing that current events are under the control of nefarious agents, conspiracy theories entail that such events are capable of being controlled.

Brian L. Keeley, „Of Conspiracy Theories”

No comments:

Post a Comment